A gift from trees.

“To enter a wood is to pass into a different world in which we ourselves are transformed.” Roger Deakin.

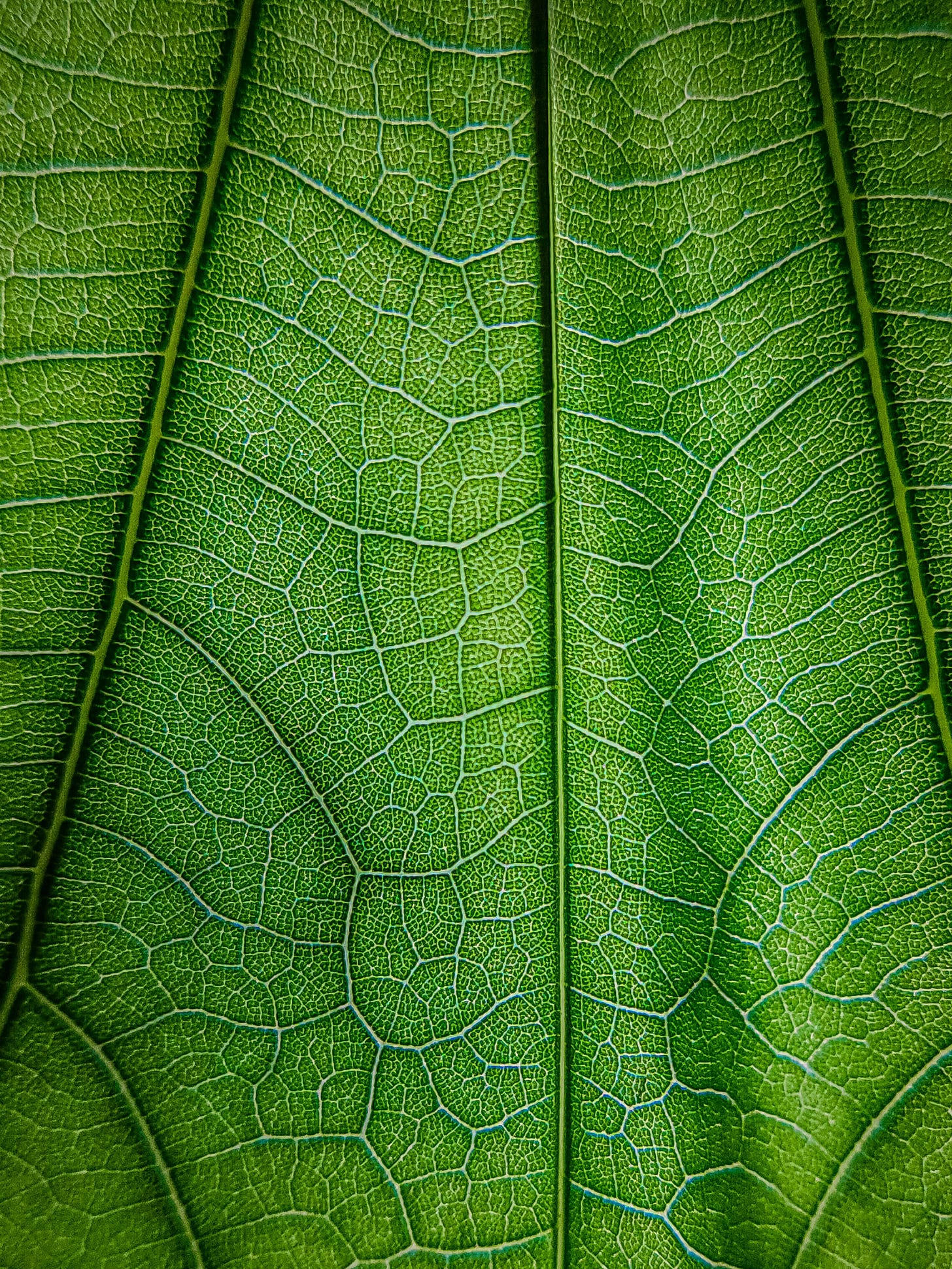

Hold a tree leaf towards the sunlight and you’ll be able to see the individual cells within it, even with the naked eye. Inside these cells the incredible, complex and insanely efficient natural process of photosynthesis is happening. The canopy of a tree is a powerhouse of photosynthesis and the leaves are consuming light energy.

Not only that, in this process water and CO2 are combined to magic oxygen for life to breathe. Of course science can explain the mechanisms of this, but when you sit beneath a tree for a moment to really think about this process, it becomes too wondrous to express in words or scientific explanation.

The ethnobotanist Tim Plowman when asked about plant intelligence and plants reaction to classical music, said, “Why would a plant care about Mozart? And even if it did, why should that impress us? They can eat light, isn’t that enough?”.

It is one of the most extraordinary processes to occur on the planet. To consume light - and to turn that into a food source that feeds life. So of course it is enough. But yet the gifts from trees continue. They give edible seeds, pre-wrapped and ready to store. Delicious fruit, nutritious leaves, medicinal bark, saps and resins, and all of that before we even start with the beauty and strength of timber. Their wood burns creating fire, the control of which changed the course of human evolution. They offer shade in the heat, shelter from the cold and are fundamental to natural water cycles. Leaves add nutrient rich organic matter to soil, while their roots stabilise and protect. As well as releasing oxygen for life to breathe, the leaves also release health enhancing phytochemicals.

Trees are the most incredible of beings - ancient, long-lived elders that nurture life and build community. People and trees have coexisted in a harmony of gifts and gratitude for thousands of years and it is clearly understandable why, in nearly every culture across the world, trees stand as sacred beings to worship and respect.

“I’m standing on the shoulders of thousands of years of knowledge. I think it’s so important that we all recognise this: that there is so much knowledge that we’ve ignored”.

― Dr. Suzanne Simard, Professor of Forest Ecology, University of British Columbia and the leader of The Mother Tree Project.

At the beginning of the 20th Century the UK’s woodland coverage was at an all time low – just 5 per cent of total land area. Two World Wars took their toll on trees as well as people and the Forestry Commission was set up to replenish what had been lost. For speed and efficiency of growth and restocking potential, foresters turned to non-native species of conifers, which were planted across the UK in large monocultures. With the rise of mechanisation it was imagined that these plantations would supply timber for the future in the most cost effective way.

And to be fair they have supplied the UK with timber and what was planted 60, 70 years ago in the time after the Second World War, is keeping the UK timber industry going today. But the negative impact to the land, to native woodlands and to biodiversity was severe. The decisions have been heavily criticised and it’s easy to see why. But conversely, those foresters were working within the confines of a nation depleted of trees and a monetary based system we have poorly imagined for ourselves.

When profit is the decision maker, the forest is a commodity. It is no longer sacred. The main aim is to weed out everything but the dominant, commercial tree species creating monocultures of even aged trees that can be efficiently clear felled. Complexity is removed to mitigate risk. Maintenance involves spraying herbicides. The clear fell harvest requires large, powerful machinery which is brutal on the soil.

I remember walking through large monocultures of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) in the Southern Uplands of Scotland during a forestry study tour a few years ago. It was harsh and the hard battle lines drawn between forestry and farmland were stark. Monoculture vs. monoculture. Unfortunately forestry in the UK is still working to those practices in some areas but it is definitely being tempered - the growth of strong scientific evidence supporting the need for a diversity of species and complex management practices allowing for multi-aged forests of mixed species and protection of ground flora and soils.

UK woodlands didn’t get to 5% overnight. What was a complex mosaic of wild wood and pasture that developed after the last ice age was gradually altered at the hand of people for thousands of years. Obviously we have seen some of the most drastic changes in more recent times but these Isles we call home have been manipulated and managed to an extraordinary extent.

I am reminded of the words of Jeremy Lent in his book ‘The Web of Meaning’ - he quotes the Joni Mitchell song Big Yellow Taxi:

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

They took all the trees

Put ‘em in a tree museum

And they charged the people

A dollar and a half just to see ‘em

Despite the song becoming iconic in the environmental movement of the late 1960s, Lent believes the words - you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone - were wrong.

Things go, maybe gradually, and then you don’t remember what it was like before. Lent says, “the disturbing reality is that, once it’s gone, people forget they ever had it”.1 In the case of the UK, the trees are gone and people even start to like the empty, lifeless landscapes. I grew up on Dartmoor, it was an incredible place to be a kid running wild, and I loved it. But it is an empty place, described by some as a ‘biological desert’ and yet people have become accustomed to the barren hills and ironically want to preserve it.

I guess the point is that it becomes too easy to ‘forget’ the abundance of life. To forget what a thriving forest landscape could be like. Or maybe a more accurate way of expressing it would be to say; we need to keep imagining what a thriving forest landscape could be like - how it would feel to be part of a place bursting and humming with life. We don’t want to lose our trees, forgotten to a museum.

Forest cover in the UK is now at about 13%. It is in a better place compared to the start of the Century. Now is the time to take a moment, to listen to the stories of the past and consider how we might tell them for the future. Silviculture is a slow and considered process. It relies on the knowledge of forester forefathers and thought for foresters of the future. In that, recognising both the positive enhancements from the past as well as the mistakes that have been made. The timescale is inherently multigenerational. It is not a process to be rushed. Planting one well thought out tree, nurturing with time, good energy and consideration is much better than a thousand badly planted, ill conceived ones.

There is so much knowledge that we can’t afford to ignore.

The past twenty years has seen incredible scientific advancements in understanding forest ecosystems - as the saying goes - it takes more than trees to make a forest. Trees are part of a community. In a thriving forest there is a nuanced and beautiful complexity of interactions both above and below ground. Multiple interspecific cooperations between plants, fungi and fauna.

For a forest to thrive in our care, foresters must change their job title from managers, to custodians of these extraordinary environments. They need to understand and abide by the natural laws and ways which afford forests resilience and allow them the freedom to adapt and preserve their own health. Combined with improvement in scientific understanding is the greater appreciation of Indigenous land practices and traditional ecological knowledge.

What Indigenous peoples have known for thousands of years about the forest and interconnecting landscapes is being proven by science - the science is only just catching up. This deep ecological knowledge, learnt through careful, meticulous observations and effective knowledge transfer, has been ignored for too long.

In the UK, on the periphery of mainstream forest management, is where creativity and imagining is happening. There are artisan foresters, woodworkers, hedge layers, coppice workers, charcoal makers, agroforesters and forest gardeners holding on tight to our traditional ecological knowledge, learning and adapting practices for the future and harvesting for abundance.

“Gratitude is most powerful as a response to the Earth because it provides an opening to reciprocity, to the act of giving back, to living in a way that the Earth will be grateful for us.

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

A thriving forest is so much more than a plantation of trees for timber. The generosity of the forest is extraordinary in its abundance and in ‘forgetting’ the potential, we have overlooked the gifts it offers. In many other parts of the world the forest is the larder, medicine cabinet, shelter and place for scared worship. When the forest offers all of that, it would be impossible not to feel an immense sense of gratitude and not to offer care and protection for the forest in return. UK forestry is improving on what was a desperate situation but our forests and wooded landscapes are not thriving - there is much work to do, much knowledge to remember and thought to put into action. By supporting the artisan forest industries, it brings more people into relation with the land and trees, their energy and skill feed the forest. When working in harmony with the land they are as much a part of that living community as any other species and their actions can enhance the forest through respectful tending, never wasting what is precious and leaving plenty for others.

We started our company - From Trees - as a way to imagine and support that relationship between people and forests.

To recognise the potential and to create a platform where we could offer respectfully harvested goods from trees to a wider community. To consider the harvests of the past, the rich ethnobotanical knowledge we hold, and how harvests might become for the future. To consider averting the focus on timber in UK forestry and how we might add non-timber harvests to the way we could holistically manage the land. And in doing so adding much needed species diversity. Our native tree species offer gifts in abundance for health, wellness and nutrition. It is utterly wondrous to think that for so much of what we need the trees, plants and fungi have an offering. And even when the forests are in poor health - like many in the UK - they still provide for us. It is without a doubt time to give back. Not in charity. But to form respectful bonds of mutual benefit so that we might exist in symbiotic relation. If we need example of how this might feel we only need look for a natural lead;

Oak gives Jay many delicious, nutritious seeds (acorns) to eat. Jay harvests the seeds. A few will be eaten straight away, many will be stored for the winter to come, and Jay will plant some for Oak in gratitude and thanks. As Jay plants seeds, Oak will have kin. And in that, their relationship will always be preserved. One of mutual benefit, respect and cooperation.

The relationship between Oak trees and Jays extends out, it is one that builds community and allows life to flourish. Imagine if we were as grateful and generous in our actions. What abundance there would be. So to return to the beginning, to Deakin’s quote:

“To enter a wood is to pass into a different world in which we ourselves are transformed.”

― Roger Deakin.

Our woodlands and forests do transform us, to be a part of them makes us feel alive, they connect us to a deep past and provide us with hope for the future. For all the gifts received from trees, how fulfilling it would be to realise the potential of a mutually beneficial relationship, allowing all to thrive collectively.

Jeremy Lent; ‘The Web of Meaning’

A Gift from Trees was originally written for The Southwester Newspaper.

Nice to read you on here Lou. I enjoyed this.